- MPA Handbook

- Chapter One

Why create a highly protected Marine Protected Area (MPA)? What are the benefits?

Learn about the many benefits of highly protected areas to marine life and people.

The ocean and people at risk

The ocean covers 70% of the Earth’s surface, but because of how deep it is, it represents about 99% of the planet’s habitable living space.1 It is home to the majority of the different types of lifeforms that exist on Earth.2 In fact, the ocean is so vast and marine life so diverse, scientists estimate that more than 90% of marine species are yet to be found,3 and more than 80% of the ocean is yet to be explored.4

Because of its bounty and vastness, people have long thought of the ocean as an inexhaustible resource.5 But as humans have become more and more capable of exploiting more and more of the ocean, moving farther offshore and into deeper waters, this assumption has been shattered. It’s now widely recognized that life in the ocean—indeed, all life on Earth—is in big trouble.

For decades, the world’s ocean has literally been “taking the heat” for the planet, absorbing over 90% of the heat and nearly a third of the carbon dioxide generated from greenhouse gas emissions.6 The result is an ocean that is warmer, more acidic, and increasingly starved of oxygen—overall, an ocean that is becoming less habitable for fish and wildlife.

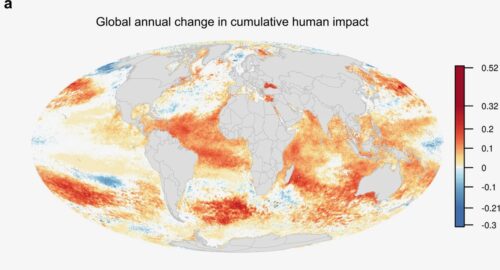

Marine life is at risk, with almost 33% of reef-forming corals and more than a third of all marine mammals threatened with extinction.7 We are losing species at a rate that is at least a thousand times higher than the natural rate of extinction of species. If we don’t address these high human impacts, we may lose entire ecosystems.8 Many of the world’s most threatened habitats and species are in the ocean, and most of the ocean is affected by humans (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Global human impact on the world’s oceans, from 2013. Impacts are from sources including fishing, shipping, pollution, and climate change-related stressors like warming, ocean acidification, and sea level rise. Coastal areas indicated with dots have finer-scale images available at Halpern et al. 2019. Source: Halpern et al. 2019. © 2019 The Author(s). Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

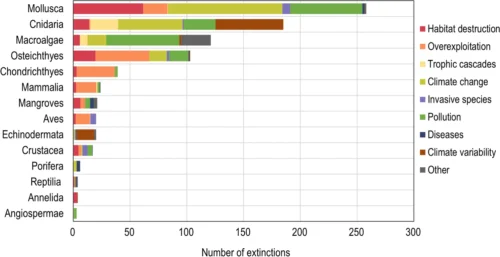

Figure 2. Number of extinctions recorded for the different taxonomic groups of marine species, with driver of extinction by color. Source: Nikolaou and Katsanevakis (2023). Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Human threats to marine life include habitat loss (by coastal development, for example), ocean warming and acidification, pollution, and the introduction of invasive species (Figure 2). However, the most important human-caused threat to ocean life has been, by far, overexploitation—that is, catching fish and other animals faster than they can reproduce.

The pace and scale of these impacts has been getting faster and more destructive in our lifetimes, with bigger implications for marine life (Figure 3). For example, human fishers have a much bigger impact than other ocean predators; we are “superpredators” that like to kill ocean predators such as sharks, groupers, and other large fishes. We are also unnaturally fast at catching prey (at a median rate that is 14 times higher than other predators).9 Because of our voracious appetites for protein and money, ocean animals with a larger body size are at higher risk of extinction.10 We have removed 90% of the large fish in the last century alone.11 Nearly every corner of the ocean has been touched by human impact or extraction, with over ⅔ of the ocean significantly altered by human activity.12 The good news is that MPAs that ban fishing help to halt overexploitation, and eventually restore what was lost, better than any other management action.

Figure 3. Timeline (log scale) of marine and terrestrial defaunation. Current ocean trends, coupled with terrestrial defaunation lessons, suggest that marine defaunation rates will rapidly intensify as human use of the ocean industrializes. Source: McCauley et al., 2015.

When we lose other species, humans suffer, too. For example, climate change-driven loss of ocean animal biomass is likely to be highest at low to middle latitudes, nearer the equator, where fisheries are often a main source of protein.13 Loss of an ecosystem like a coral reef is a tragedy even for those of us who do not live near a reef, but it can have repercussions that can be catastrophic for nearby communities. Coral reefs, as well as other threatened ecosystems such as mangroves and seagrass beds, provide important, hidden benefits for people, such as protection from storms, coastal erosion, and flooding (see below for more on benefits for people and nature).

The ocean provides many other hidden benefits, too—from absorbing more than 90% of the heat from human-caused greenhouse gas emissions, to providing more than half of the oxygen we breathe. Protecting ocean habitats allows them to continue to provide these hidden benefits, which we all rely on.

Citations

- Costanza, R. The Ecological, Economic, and Social Importance of the Oceans. Ecological Economics 31, 199–213 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00079-8

- Sullivan, J. M., Constant, V., & Lubchenco, J. Extinction Threats to Life in the Ocean and Opportunities for Their Amelioration. In Biological Extinction: New Perspectives (eds Mclvor, A., Dasgupta, P., & Raven, P.) 113–137 (Cambridge University Press, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108668675.007

- Mora, C., Tittensor, D. P., Adl, S., Simpson, A. G. B. & Worm, B. How Many Species Are There on Earth and in the Ocean? PLOS Biology 9, e1001127 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. How Many Species Live in the Ocean? National Ocean Service National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/ocean-species.html (accessed April 9, 2025).

- Lubchenco, J., & Gaines, S. D. A New Narrative for the Ocean. Science 364, 911–911 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay2241

- The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/ (2019).

- IPBES. Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services. (eds. Brondizio, E., Settele, J., Díaz, S., & Ngo, H. T.) 1–1148 (IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany, 2019). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3831673

- Lubchenco & Gaines, A New Narrative for the Ocean, 911.

- Darimont, C. T., Fox, C. H., Bryan, H. M. & Reimchen, T. E. The unique ecology of human predators. Science 349, 858–860 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4249.

- Payne, J. L., Bush, A. M., Heim, N. A., Knope, M. L. & McCauley, D. J. Ecological selectivity of the emerging mass extinction in the oceans. Science 353, 1284–1286 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf2416.

- Myers, R. A. & Worm, B. Rapid worldwide depletion of predatory fish communities. Nature 423, 280–283 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01610

- The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, (2019).

- Lotze, H. K. et al. Global ensemble projections reveal trophic amplification of ocean biomass declines with climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, 12907–12912 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1900194116