- MPA Handbook

- Chapter One

Why create a highly protected Marine Protected Area (MPA)? What are the benefits?

Learn about the many benefits of highly protected areas to marine life and people.

Benefits for people

Less than two kilometers off the most north-east coast of Spain, in the beautiful Costa Brava, sit the Medes Islands (Illes Medes in Catalan). Made up of craggy islets, this archipelago is one of the most beautiful ocean ecosystems in the western Mediterranean, and it’s also one of its most protected. Since its designation in 1983, the Medes Islands Marine Reserve has become a haven for ocean lovers from around the world. SCUBA divers, snorkelers, kayakers, sailors, and glass bottom boat tourists alike flock to the park to see rare red coral, swim through beautiful underwater tunnels, hang out with giant dusky groupers, and watch seabirds make their nests on the islands. Fishing is prohibited or highly controlled within much of the park, and designated buoys to moor boats and kayaks throughout the MPA make it easier for visitors to enjoy—but not damage—the fragile habitats.

This small marine park has led not only to a thriving and vibrant marine ecosystem, but a robust tourism industry. Less than one square kilometer of full protection is providing the local community with over 250 additional full-time jobs, and in 2007, it brought 12 million Euros of tourism revenue to the region.1 (In 2024, it was closer to 16 million Euros.) This tourism revenue was 20 times more than the cost of managing the reserve, and 30 times more than the area’s fishing revenue.2

While this example highlights the substantial benefits MPAs offer through tourism, highly and fully protected MPAs provide a wide range of benefits for people. According to studies, every dollar invested in an effective MPA returns between $10 and $20 in multi-faceted benefits.34

When they are designed and managed well, MPAs can be powerful tools for promoting economic and human well-being, resulting in:

- Better local fisheries,

- more revenue and jobs,

- improved health, and

- cleaner and safer coasts.

We discuss each of these benefits in more detail below. Some of these benefits will be instantaneous (e.g., tourism benefits that come with the implementation and publicity of the MPA), but others will take time to realize. Furthermore, not all people will benefit equally, or at the same time in the same ways.

The MPA must be managed carefully so that its ability to restore marine life is maintained over time. Whether benefits are realized, and how quickly, also depends on the effectiveness of the MPA: how well-managed and enforced it is. It is also influenced by the size of the MPA and what’s allowed within. When well-designed and resourced, however, the short-term costs of MPAs can be minimized and outweighed by the long-term benefits.

1. Better fisheries

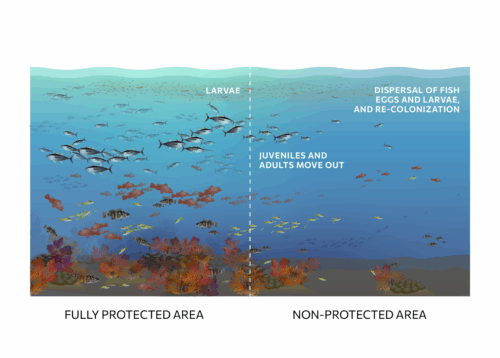

By removing human pressures like fishing from a specific area, MPAs generate more, and bigger, fish that produce more, healthier babies (see “Benefits for Nature”). The rapid population growth and recovery within an MPA’s boundaries then lead to a “spillover effect,” where larger and more abundant fish and their babies move from within the protected area to nearby areas, replenishing fish abundance and boosting fishers’ catch outside the MPA (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Illustration of the spillover effect. Source: Authors.

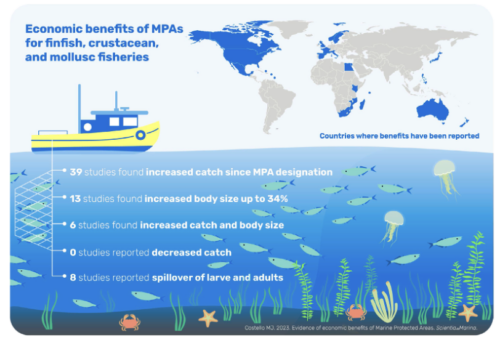

Figure 11. Summary of economic benefits of MPAs for fisheries, from a 2024 study of 81 publications about MPAs in 37 countries. Source: Costello, M.J., 2024. © 2024 Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC). Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Fisheries benefits have been shown to occur within as little as three years after an MPA is established, although long-lived and slow-growing species can take a decade or more to recover (Figure 11). These benefits are most noticeable and consistent when MPAs are located in areas where overfishing or overexploitation has occurred. The “spillover effect” (Figure 10) has now been documented for MPAs and fisheries around the globe—from the spiny lobster fishery in southern California5 6 (detailed in a Case Study) to tuna fisheries in the Central Pacific.7 Note that in southern California, lobster catches more than doubled within 6 years near MPAs, but the same change did not occur far from the MPAs. California’s fisheries are among the most managed in the world, yet fully protected MPAs bolstered catches, which shows that MPAs can achieve recoveries that fisheries management alone cannot.

The spillover effect doesn’t just benefit commercial fishers, but also recreational fishers and sportfishers as well. For example, research has shown fully protected MPAs disproportionately produce world record-setting fish catches for sportfishing competitions around the world.8

Adding an MPA to a place where people rely on fishing can also help communities follow the “precautionary principle”—basically, the MPA serves as an insurance policy or safety net for the whole area in the event of unexpected challenges. For example, a big storm, or a warm water or low oxygen event, might reduce the population numbers of an important fishery species. If fisheries management is not adjusted accordingly, these species could continue to be fished at the same rate, despite having fewer individuals in the population. This can very quickly lead to overfishing, and even fishery collapse. But with an MPA in the area, some individuals of the population can be shielded from a slow or inadequate response in fishery management or the added pressure of fishing. These protected individuals will be able to continue to grow and reproduce, thus helping the overall population recover faster.

2. More tourism jobs and revenue

Photo credit: Oral Berat User

Whether in the rocky Medes Islands of Spain, the coral reefs of the Philippines, or the towering kelp forests of New Zealand, people are drawn to the healthy marine life found in MPAs. These places provide bigger and more plentiful fish, diverse and thriving wildlife, healthy and intact habitats, and perhaps even the chance to see rare and unique species. Tourists’ preference to visit protected areas over other ocean areas is widely known within the tourism industry, and has been documented in scientific literature.9 By supporting vibrant ecosystems and offering a place-based connection to nature, MPAs provide an unparalleled opportunity for coastal communities to tap into the global economic engine of ecotourism (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Summary of economic benefits of MPAs for tourism. Source: Costello M.J. 2024. © 2024 Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC). Licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Ecotourism is among the largest sectors in the ocean economy, making up at least 50% of all global marine tourism.10 Dive tourism alone supports 124,000 jobs worldwide, providing experiences for up to 14 million tourists and a global economic impact of up to US$20 billion per year.11 Often, these revenues greatly overshadow those generated through extractive industries like fishing. In Palau, tourism is more profitable than fishing: shark tourism contributes about US$18 million a year to the economy of Palau, whereas shark fishing would contribute only US$10,800.12 In the Galápagos Islands, the average annual value of a shark to the tourism industry is US$360,105—when considering a shark’s entire lifespan (around 23 years for most sharks in the Galápagos, when undisturbed), the tourism spending generated by a single shark over its lifetime is estimated at US$5.4 million. As a point of comparison, the maximum value a shark can fetch when sold on the mainland for its meat and fins is less than US$200.13

However, it is also important to keep in mind that too much tourism, without sustainable measures in place, can result in harm for ocean wildlife and local communities.

See “How do we Fund our MPA?” for more on economic benefits, as well as considerations to ensure sustainable tourism within MPAs are benefitting—and not harming—wildlife and local communities. For more real-world examples of these ideas in action, see the Case Studies section.

3. Healthier people and communities

MPAs can also promote healthy ecosystems that support people’s livelihoods, identities, physical and mental health, and well-being.14 For instance, MPAs can benefit human health and well-being through:

- Healthier fisheries: More fish resulting from an MPA can also mean more food on the table, leading to better food security for local communities. In fact, in developing countries, living near an MPA has been linked to improved childhood health.15 During the COVID-19 pandemic, the abundance of fish inside the Apo Island MPA in the Philippines provided food security during this period of hardship for local residents, providing health and nutrition for many islanders (personal communications).

- Biomedical discoveries: Intact ecosystems in MPAs can lead to new medicines, technologies, and genetic material discovered through scientific research, all of which can be used in products that help improve human health and well-being. For example, while exploring a fully protected area in the Southern Pacific Ocean, scientists on the R/V Falkor observed some lesions on a deep-sea coral and took a non-invasive swab with a remotely operated vehicle (ROV). They later discovered that the bacteria isolated from the swab can help more safely deliver biomedical drugs in humans.16 Protected areas can help make sure these resources remain undisturbed, as well as enable scientific discoveries for the benefit of future generations—provided that the country gives permission with clear rules and permitting, the scientific research is well-managed and minimally invasive, and there are plans in place for the sustainable extraction of any discoveries.

- Protection of cultural and spiritual identities and practices: MPAs around the world can protect cultural landscapes from development and allow for the continuation of cultural practices and spiritual well-being. One example of this is the Buccaneer Archipelago Marine Parks (Mayala and Bardi Jawi Gaara Marine Parks) in Western Australia, which were co-designed and are now jointly managed by Traditional Owners alongside the Government of Western Australia. Rich with cultural significance, the zoning of the parks ensured that areas of particular conservation and cultural significance were both protected. The Bardi Jawi Gaarra Marine Park is “used consistently by Bardi and Jawi people for hunting and fishing for food, cultural activities and business.”17 See the Case Studies section for more detailed information about Buccaneer Archipelago Marine Parks.

Photo credit: Oral Berat User

4. Cleaner and safer coasts

Photo credit: Alex Mustard

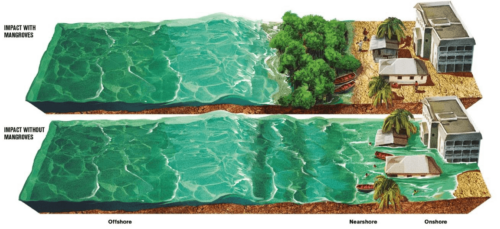

In 2013, the Philippines was hit by Super Typhoon Yolanda, one of the most powerful tropical storms ever recorded. Whole cities and towns were destroyed by 16 to 20 foot waves, extreme winds, and severe flooding, and at least 6,300 people lost their lives. But some coastal towns directly in the path of the storm were spared, even while neighboring towns and cities just up the road were completely leveled. Residents, government officials, and scientific analyses attributed this to the extensive mangrove forests that offered these coastal towns special protection.18 Since then, the Philippines has prioritized restoring and protecting mangrove forests around the country. For example, the Del Carmen municipality is one of many that are protecting mangrove forests and cracking down on illegal mangrove logging.

Figure 13. Impact of storms on coastal communities with and without the protection of intact mangrove forests. Source: Ortega, Saul Torres; Losada, Inigo J.; Espejo, Antonio; Abad, Sheila; Narayan, Siddharth; Beck, Michael W.. 2019. The Flood Protection Benefits and Restoration Costs for Mangroves in Jamaica. Forces of Nature;. © World Bank. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/35166 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.

MPAs promote the health of nearshore habitats like mangroves, seagrasses, and kelp beds—all natural infrastructure that, when intact, can be much stronger than human-built “gray” infrastructure. These important habitats can help to keep coastal communities safe and healthy by:

- Shielding against storms and flooding: Mangroves, wetlands, and coral reefs provide protection from storm surges by serving as natural barriers for the coast. They reduce the height of the waves passing through vegetation and coral structures, and slow down wind and water before it reaches the shore (Figure 13).

- Serving as natural filtration systems: Coastal ecosystems like mangroves, seagrass beds, oyster reefs, and wetlands also filter the water, removing harmful bacteria. One study found that the seagrass meadows of inhabited atolls near Sulawesi, Indonesia, helped to improve water quality in the face of human-caused bacteria, and also protected nearby reefs from coral and fish diseases.19

- Locking up toxic chemicals: Studies have found that mobile fishing gear like dredging or bottom trawling can resuspend sediments and legacy pollutants (e.g., DDT, PCBs, heavy metals) in the water column at a higher rate than natural disturbances, reintroducing them to food webs. MPAs that prohibit these gear types help lock up these toxic chemicals in bottom sediments and vegetation so they are not ingested or absorbed by marine life (or by people, when we eat those fish).

MPAs are like investing in the principle of savings accounts. If we protect our capital, the services that nature provides to humanity grow, and we can continue to enjoy dividends (the “spillover”) for generations to come. But if we keep using up nature’s resources without replenishing them and erode the principle, we will have spent all our savings until there is nothing left. Nature will be bankrupt, and so will we. For more economic principles and how to fund an MPA, see Chapter 3.

Citations

- Merino, G., Maynou, F. & Boncoeur, J. Bioeconomic model for a three-zone Marine Protected Area: a case study of Medes Islands (northwest Mediterranean). ICES Journal of Marine Science 66, 147–154 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsn200

- Sala, E. et al. Fish banks: An economic model to scale marine conservation. Marine Policy 73, 154–161 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0058799

- Brander, L. et al. The Benefits to People of Expanding Marine Protected Areas. 1–190 https://www.issuelab.org/resources/25951/25951.pdf?download=true&_ga=2.227198557.1167454837.1558640107-1857028723.1558640107 (2015).

- Barbier, E. B., Burgess, J. C. & Dean, T. J. How to pay for saving biodiversity. Science 360, 486–488 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aar3454

- Lenihan, H. S., Fitzgerald, S. P., Reed, D. C., Hofmeister, J. K. K. & Stier, A. C. Increasing spillover enhances southern California spiny lobster catch along marine reserve borders. Ecosphere 13, e4110 (2022).https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.4110

- Lenihan, H. S. et al. Evidence that spillover from Marine Protected Areas benefits the spiny lobster (Panulirus interruptus) fishery in southern California. Sci Rep 11, 2663 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-82371-5

- Medoff, S., Lynham, J. & Raynor, J. Spillover benefits from the world’s largest fully protected MPA. Science 378, 313–316 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abn0098

- Franceschini, S., Lynham, J. & Madin, E. M. P. A global test of MPA spillover benefits to recreational fisheries. Science Advances 10, eado9783 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ado9783

- Morse, M. et al. Preferential selection of marine protected areas by the recreational scuba diving industry. Marine Policy 159, 105908 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105908

- Northrop, E. et al. Opportunities for Transforming Coastal and Marine Tourism: Towards Sustainability, Regeneration and Resilience. (2022).

- Schuhbauer, A. et al. Global economic impact of scuba dive tourism. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2609621/v1.

- Vianna, G. M. S., Meekan, M. G., Pannell, D. J., Marsh, S. P. & Meeuwig, J. J. Socio-economic value and community benefits from shark-diving tourism in Palau: A sustainable use of reef shark populations. Biological Conservation 145, 267–277 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2011.11.022

- Lynham, J., Costello, C., Gaines, S. & Sala, E. Economic Valuation of Marine- and Shark-based Tourism in the Galápagos Islands. (2015)

- Ban, N. C. et al. Well-being outcomes of marine protected areas. Nat Sustain 2, 524–532 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0306-2

- Fisher, B. et al. Effect of coastal marine protection on childhood health: an exploratory study. The Lancet 389, S8 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31120-0

- Anna E. Gauthier et al. Deep-sea microbes as tools to refine the rules of innate immune pattern recognition. Science Immunology 6, eabe0531. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.abe0531

- Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions. Bardi Jawi Gaarra Marine Park. https://www.dbca.wa.gov.au/management/plans/bardi-jawi-gaarra-marine-park.

- Seriño, M. N. et al. Valuing the Protection Service Provided by Mangroves in Typhoon-Hit Areas in the Philippines. 1–35 (2017).

- Lamb, J. B. et al. Seagrass ecosystems reduce exposure to bacterial pathogens of humans, fishes, and invertebrates. Science 355, 731–733 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal1956